What “foreign currency account” means in practice

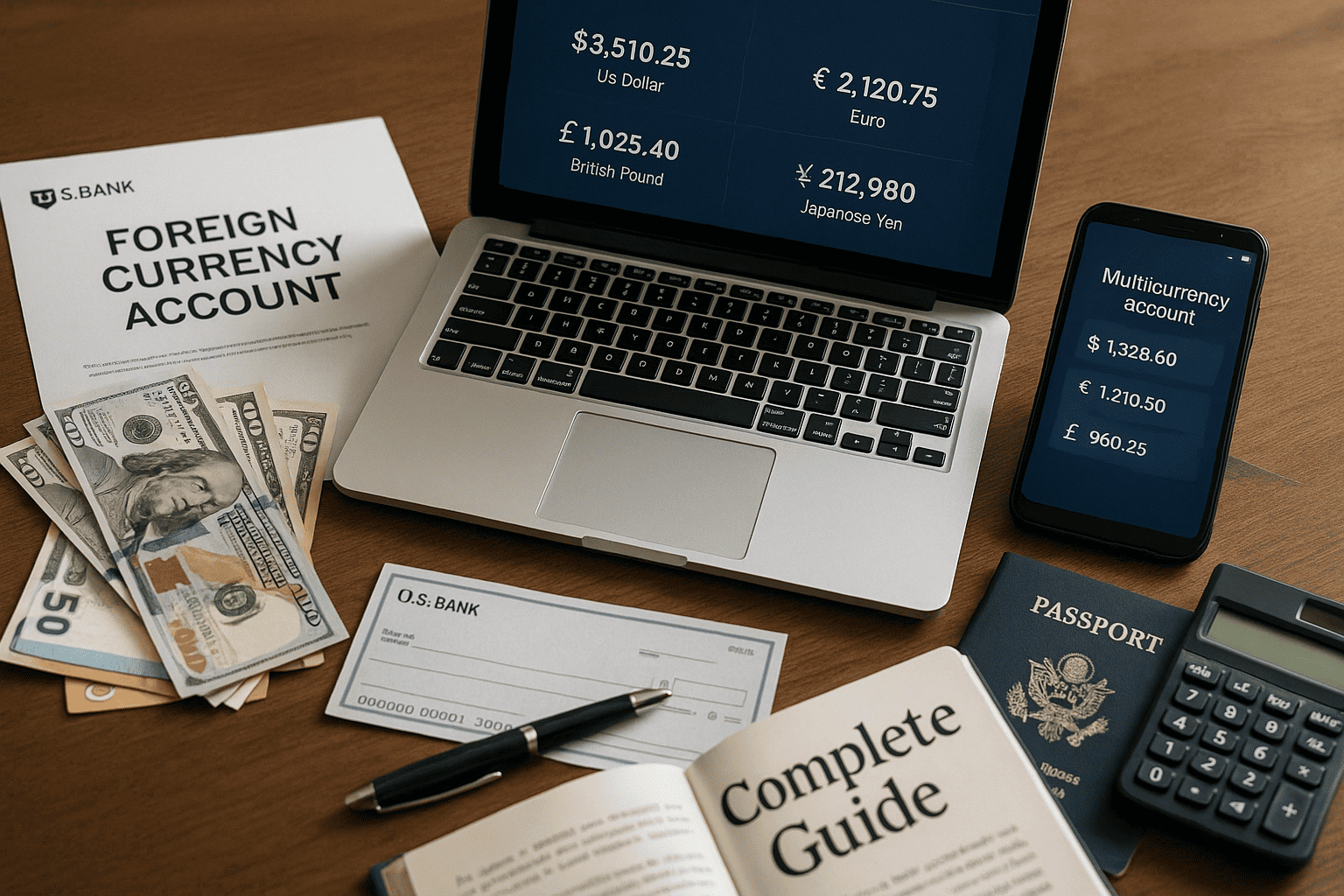

A foreign currency account can be either single-currency (for example, an account that holds only euros) or multi-currency (a single relationship that maintains separate balances in several currencies). Practically speaking, three delivery models dominate the market:

- Domestic bank foreign-currency deposits (accounts held at a U.S. insured depository institution that accept deposits in foreign currencies or that provide foreign-currency services).

- Offshore foreign accounts (accounts held directly at a non-U.S. bank).

- Non-bank multi-currency wallets and accounts provided by money-service firms and fintech platforms that enable holding and converting many currencies without being a traditional bank.

These models differ in liquidity, cost, and legal treatment. For many U.S. residents the principal trade-offs are access to near-market exchange rates, deposit protection, and compliance obligations.

Who offers foreign currency accounts to U.S. customers?

Most retail U.S. banks do not maintain consumer foreign currency accounts. As one industry practitioner observed, “Most major US banks don’t offer foreign currency accounts to personal customers – they typically reserve these services for business clients or high-net-worth individuals.” That observation has been repeated across consumer-facing guides covering U.S. availability.

A small set of U.S. banks and bank brands do provide foreign-currency demand deposits, certificates of deposit in foreign currencies, or currency exchange services; examples include East West Bank and selected international banks with U.S. operations that offer specialized products for certain customers. East West Bank documents its personal foreign-currency deposit services and foreign currency exchange at branch locations.

Fintech alternatives have become the most visible option for individuals and small businesses. Firms such as Wise allow U.S. users to hold and convert dozens of currencies in a single account and advertise conversion at or near the mid-market exchange rate; Wise describes its product as an “international account” that can hold 40+ currencies and provide local account details. That offering is not a bank deposit in the traditional sense — Wise operates as a money-service business in the U.S. and, where relevant, operates in partnership with sponsor banks for certain features.

Regulatory and deposit-insurance implications

Deposit protection and regulator status are core considerations. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) explains: “Deposit insurance coverage is provided for deposits in an IDI that are denominated in a foreign currency.” The FDIC converts foreign-currency deposits to U.S. dollars for insurance-limit purposes using published exchange rates. That means a foreign-currency deposit at an FDIC-insured bank can be insured up to the same statutory limits as dollar deposits, expressed in the dollar equivalent.

By contrast, many fintech multi-currency wallets are not bank deposits. Firms that are not banks typically hold customer funds with partner banks or in custodial arrangements; users should read program terms carefully to determine whether balances are held as insured deposits or safeguarded in another way. Wise’s public materials clarify that it is not a bank in the U.S. and that some program features rely on sponsor banks; account protections differ from FDIC insurance in structure and scope.

Tax and reporting consequences

Holding money with a foreign institution or in a foreign currency can trigger U.S. reporting obligations. FinCEN’s guidance is direct: “A United States person that has a financial interest in or signature authority over foreign financial accounts must file an FBAR if the aggregate value of the foreign financial accounts exceeds $10,000 at any time during the calendar year.” That filing is made on FinCEN Form 114 and is separate from federal income-tax filings.

The penalties for failing to comply can be material. As a longstanding consumer finance primer put it bluntly, “Not filing the FBAR has steep penalties. You can be fined as much as $100,000, or half the amount in the foreign account, whichever is greater.” Tax-sensitive customers should consult a qualified adviser before opening offshore accounts or aggregating non-U.S. balances.

FATCA and Form 8938 may also apply when the taxpayer’s specified foreign financial assets exceed statutory thresholds; those rules have separate filing thresholds and documentation requirements provided by the IRS.

Costs, spreads, and where money is converted

Three distinct fee lines determine the economic outcome of holding or using foreign currencies:

- Spread on conversion — the difference between the interbank mid-market rate and the rate provided to the customer. Fintech providers often advertise mid-market conversions with an explicit small fee; traditional banks typically embed a wider spread. Wise, for instance, markets conversions at the mid-market rate with a visible conversion fee.

- Account maintenance and service fees — monthly maintenance, minimum balances, transaction fees and inactivity charges vary by provider. Traditional banks offering these services tend to require higher balances or premium relationship status.

- Operational transaction fees — incoming/outgoing wire fees, ATM withdrawal fees, or local payment fees. These often dominate the total cost for cross-border payments and must be layered into any cost comparison.

Consumers should price all three elements for representative flows (one-off transfers, monthly receipts, ATM withdrawals) to find the reasonable cheapest path for their use case.

Typical use cases and matching the product

- Freelancers and small exporters: A multi-currency fintech account that provides local receiving details and inexpensive conversion often reduces transfer fees and reconciliation friction for low-value but frequent receipts. Wise and Payoneer are common examples for this class of use case.

- Frequent travelers: A card linked to a multi-currency wallet or a foreign-currency debit product reduces dynamic currency conversion costs and may avoid repeated conversion penalties.

- Savers or investors seeking foreign yield: Foreign savings deposits and currency CDs can offer rates not available domestically, but currency risk and transaction fees can offset interest; regulatory protections vary with where and how the account is held. Investors must model net real returns after conversion and tax. See the Investopedia review for a succinct treatment of the trade-offs and tax filing obligations.

- Businesses with cross-border payroll or supplier payments: Domestic banks with foreign-currency deposit capabilities or specialist FX providers are frequently the better option because of integrated treasury services, hedging and higher payment limits. East West Bank and other providers target this segment.

How to open and what to check (practical checklist)

- Confirm legal status: determine whether the product is a bank deposit (FDIC insured) or a non-bank safeguarded balance. If FDIC insured, check which currency denomination is covered and how the FDIC converts the balance to USD for insurance purposes.

- Read fee schedules: compare spread, inbound/outbound wire fees, card transaction fees and ATM charges on realistic transaction sizes.

- Verify identity and tax requirements: collect the documents the provider requires, and confirm whether FBAR or Form 8938 disclosures will be triggered by expected balances.

- Understand withdrawal mechanics: if holding balances offshore, review how quickly funds can be repatriated and the costs to do so.

- Check minimums and relationship requirements: some bank products require premium status or high minimums that make them impractical for consumers.

Risks and operational cautions

Primary risks include currency volatility, counterparty risk (insolvency or restrictions at the holding institution), and reporting errors that result in penalties. Non-bank custodial arrangements can provide operational convenience but do not carry FDIC deposit insurance in the same form as a U.S. bank deposit. For accounts outside the United States, political and exchange-control risks may also apply.

Final Considerations

A foreign currency account can deliver clear, measurable benefits for specific use cases — cross-border income, supplier payments, travel logistics and currency diversification. Yet the decision requires a composite assessment: legal status of the funds, regulatory protections (FDIC insurance if applicable), fee structure (spread, transaction fees, maintenance), tax-reporting obligations (FBAR and FATCA) and operational convenience. A pragmatic approach begins by mapping the expected money flows, then matching those flows to the product that minimizes combined spread, fees and compliance risk for that pattern. For many individual U.S. customers, modern multi-currency fintech accounts offer the best balance of access, transparency and low conversion cost; for corporate users or those with larger balances, bank foreign-currency deposit products and specialist treasury services remain relevant options. The essential tasks for any prospective accountholder are to confirm the provider’s legal and insurance status, price representative transactions end-to-end, and document any cross-border positions for tax compliance.

Primary sources and further reading: Wise — International / Multi-currency account; FDIC — Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (see guidance on foreign-currency deposits); FinCEN — FBAR filing guidance; Investopedia — foreign accounts and FBAR; East West Bank — foreign currency services.